Green Agriculture, Utilising Corn Residue as a Climate Adaptation Effort

The constantly changing conditions on Earth mean that people must continuously strive to develop their knowledge. New knowledge equips humans with the ability to survive in the face of these changes. Long-standing human practices, including those in the agricultural world, must inevitably change as well.

This article contains two stories from Poso and North Morowali Regencies about corn farmers who are trying to preserve the environment using corn stalks and leaves. Natanael in Poso and Asmar in North Morowali manage these corn harvest residues in different ways as an effort to apply more environmentally friendly green agriculture, which people now refer to as climate-smart agriculture.

Natanael: Using Corn Stalks and Leaves as Mulch

For a long time, many farmers have practised burning leftover garden waste that can no longer be used. In corn farming, this is the stalks and leaves. Burning these stalks and leaves not only pollutes the air with smoke but also damages certain particles in the soil, affecting its fertility. Of course, this practice also contributes to greenhouse gas emissions.

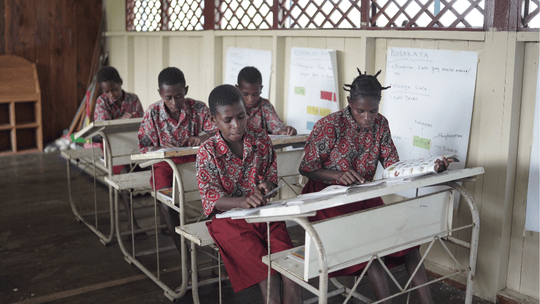

In Poso Regency, Central Sulawesi, Wahana Visi Indonesia (WVI), through its INCLUSION programme, provides assistance to several farmers on this matter. A number of farmers attended a session on how to manage corn stalks and leaves into mulch. Mulch is a material placed on the soil surface around plants to maintain soil moisture, suppress weed growth, and increase soil fertility. Natanael is one of the few farmers who diligently strives to use his corn stalks and leaves as mulch, hoping to maintain his soil's fertility. After harvesting, he cuts the stalks and leaves and places them between the rows of soil where new seeds will be planted.

"At first, there was no noticeable difference; we just got rid of the smoke. But by the third corn planting, we really felt it. Our corn plants were still growing well and weren't stunted, without having to work the soil again," Natanael explained, detailing the benefits of using this method.

The stable growth of the corn in the third planting caught the attention of other farmers. They wondered what fertiliser this father of three was using on his land. When Natanael explained that he wasn't using any fertiliser, the other farmers became interested.

Natanael and the other farmers often gather and chat in the evenings. During these gatherings, he always encourages them to talk about farming. 'Sharing knowledge and experience' is the term he uses. And it's true, when they discuss who is planting what, what the results are like, why one person is getting a better yield than another, and so on, knowledge is shared. Now, more and more farmers are adopting Natanael's method after seeing the condition of his soil.

With consistent corn yields over three harvests, Natanael's income has naturally increased. "Especially with these quality hybrid seeds, they produce better results on my land compared to local corn. Some of them rot, but more of them can withstand the current weather (with a lot of rain)," he says.

Natanael uses his corn harvest for his household's needs. His three children have all finished high school. They decided not to go to university, even though their parents had suggested it. "We just want to be free and be farmers," said his second and third children. The freedom they're referring to is the independence farmers have to set their own work pace. They imagine that if they had to work for someone else, everything would be controlled. Meanwhile, the eldest chose to work in the automotive field, which aligns with his vocational high school major.

"We can't stop them," Natanael and his wife said. In a way, they're happy because while other people are worried about who will continue to manage their farms, this couple feels at peace because their own children have the initiative to become farmers. We all know that most young people, even those from villages with parents who are farmers, choose to leave their villages because they feel that farming is not a promising or clean job.

"If everyone becomes an employee, who will plant the vegetables?" Natanael's wife asks. They are both right; with children who aspire to be farmers, they don't need to rush into converting their entire farm to perennial crops just because they can no longer manage staple crops. They have also started planting cocoa and other perennial crops, but only as a sideline.

When asked again about his hopes as a farmer, Natanael said he hopes more people will plant and manage their farms and crops in an eco-friendly way. "We use what nature gives us, and give back to nature. Besides, corn doesn't need soil that's too clean. In fact, with the stalks and leaves, weeds find it harder to grow. And if we burn the stalks and corn, we don't know what we're killing in the soil because of the heat from the fire."

Natanael says that he himself didn't initially believe in the benefits of this mulch, but after proving it for himself, he intends to spread the word to more farmers so they follow his lead. All the land on the face of the Earth is connected, let alone just within the same district. So if one plot of land is damaged, it will affect the fertility of other soil around it. He doesn't want that to happen. Maintaining soil fertility and ecosystem balance is a human responsibility, he believes.

Asmar and the Effort to Make Cattle Feed from Corn Harvest Residue

Asmar is a rather unique farmer. Almost all other farmers are people who have dedicated their time, energy, and expertise to agriculture from a relatively young age. But this man is different. He decided to return to his wife's village in North Morowali Regency after retiring from his job as a radio journalist and travelling throughout Indonesia. He gained his wealth of knowledge in agriculture from meeting and interviewing farmers, including those he found most impressive: the rice farmers in Takalar and Gowa, South Sulawesi.

Starting a career as a farmer at an older age was quite a challenge for Asmar. He admits that when he returned to the village in 2021, he started farming by trial and error. "I was a farmer's son back in my own village, although I had never been a farmer myself. I was away for more than 25 years, travelling around Indonesia as a radio journalist, so there were many new things, and I had to try everything from scratch again," Asmar explained.

His introduction to WVI was quite helpful for Asmar in starting his new career as a farmer. When WVI first came to the village, the field team conducted separate interviews with each couple participating in the programme. During these interviews, everyone was asked about many things, including their future dreams and the type of farming they were doing. After the initial interviews, some corn farmers decided to work together and formed a group called Ganduwatu. 'Gandu' means corn, and 'watu' can be interpreted as a hard stone but also represents the name of one of the Mori sub-tribes, where the majority of the villagers live. The group members chose Asmar as their leader. "I told them I had no experience as a farmer, but they said I was experienced because I had met so many people," Asmar explained the process of being chosen as the leader.

One of the interesting things when visiting Asmar's house is the many blue drums next to it. When asked what was inside, Asmar explained in detail. In this village, besides many corn farmers, a significant number of residents also raise cattle. "There are about a thousand cows in this village," Asmar said. This became one of the WVI team's focuses for collaboration. Previously, corn farmers would just burn the leftover corn stalks and leaves from the harvest. Some were used as animal feed, but because there was too much, most of it would rot before being eaten by the animals. This situation is a real shame because the rotting plants can release methane, which contributes to the greenhouse effect.

Asmar and other corn farmers then learned a new method for processing the corn stalks and leaves to make silage, which is fermented livestock feed made from corn leaves and stalks. When asked about the benefit of feeding cows with this silage, Asmar tried to explain. "Before, the stalks and leaves that couldn't be given to the cows were burned. With this silage, we can use everything. The stalks and leaves are preserved. I've checked, and it turns out they can last for up to eight months in these drums," he explained.

This silage is not given to the cows on its own. The cows in this village are used to eating fresh leaves directly from the trees. The benefit is that the farmers don't have to worry too much about their feed. But when the dry season comes, farmers can struggle because they have to look for feed in distant locations where there is still plenty of green grass. With silage, there is at least a reserve of livestock feed, although it must still be mixed with fresh leaves.

For Asmar and his farming group, this new knowledge is very helpful. With the stalk and leaf chopper machine provided by WVI, they work together to make silage, which in the future will be focused on fattening cattle. "At first, the cows just ignored the silage that was mixed with fresh leaves that we gave them. Maybe they weren't used to it. But after we figured out a trick, they ate it all," Asmar explained the challenge he faced when he first gave the cows silage. Initially, the livestock, besides being left to roam freely on the farm, only got salt water as an extra supplement.

The current challenge still faced by Asmar and other corn farmers in his village is the weather conditions. Their village has often been flooded over the past two years when it rains heavily. The river overflows and submerges the corn plants. In 2024, the flood didn't recede for days, so this father of two and several other farmers whose land was nearby were forced to cut down the corn plants that had no chance of bearing fruit and turn the leaves into cattle feed.

On other days, when a relentless drought comes, farmers also have difficulty balancing between preparing leaves for cattle feed and ensuring the corn plants grow well to produce a maximum yield. The villagers face each of these challenges together. Although they don't always find a solution, they continue to learn.

For Asmar and the Ganduwatu farming group, the most important thing now is that they have new knowledge and hope. They know that this silage has been proven in other places to be a great feed for fattening livestock, especially cows. They hope that one day they will find their own formula to profit from this silage. In addition, one thing that excites them is that the farmers in this village, like Natanael from Poso Regency, are already contributing to reducing the impact of the climate crisis on agriculture by not burning corn stalks and leaves.

Author: Dian Purnomo (Writer and researcher, consultant for INCLUSION bulletin for Central Sulawesi area)

Editor: Mariana Kurniawati (Communication Executive)